Understanding Xwayland - Part 2 of 2

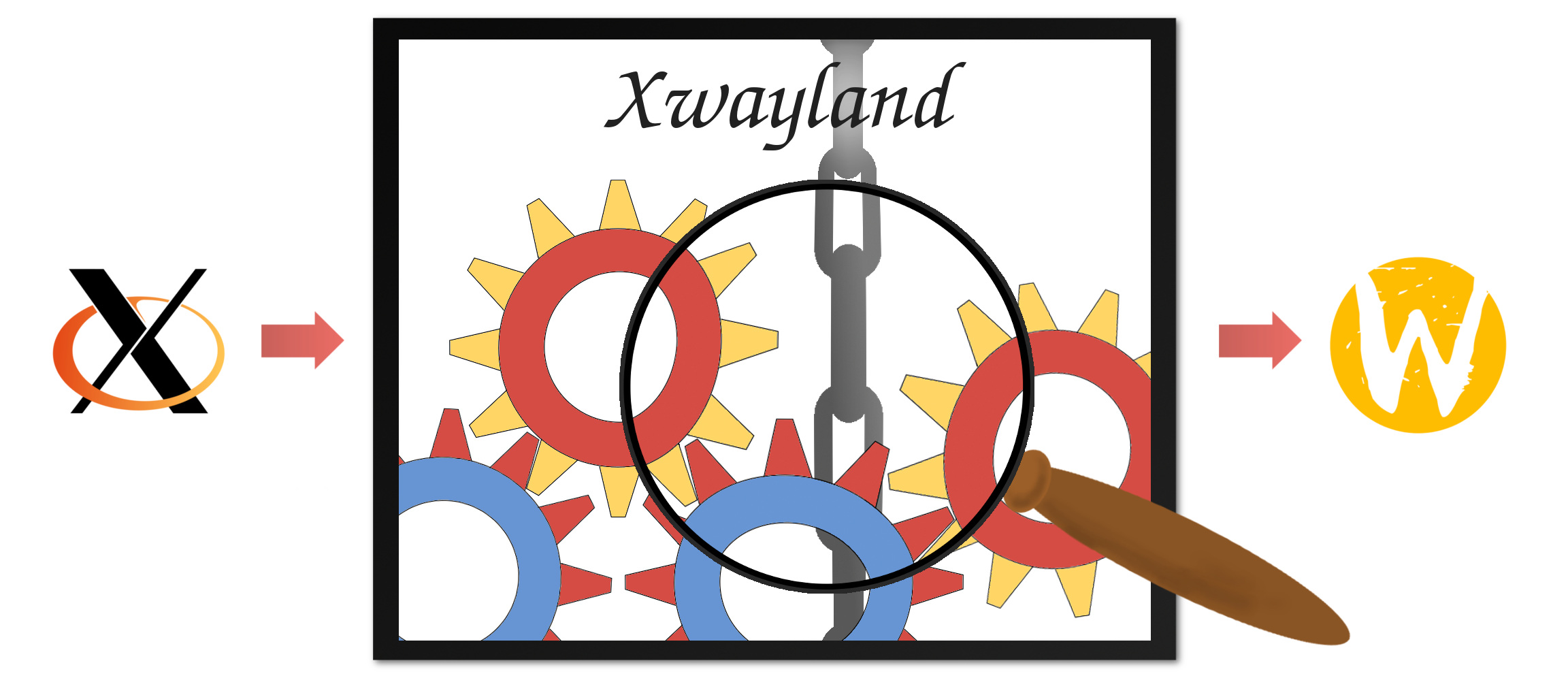

Last week in part one of this two part series about the fundamentals of Xwayland, we treated Xwayland like a black box. We stated what its purpose is and gave a rough overview on how it connects to its environment, notably its clients and the Wayland compositor. In a sense this was only a teaser, since we didn't yet look at Xwayland's inner workings. So welcome to part two, where we do a deep dive into its code base!

You can find the Xwayland code base here. Maybe to your surprise this is just the code of X.org's Xserver, which we will just refer to as the Xserver in the rest of this text. But as a reminder from part one: Xwayland is only a normal Xserver "with a special backend written to communicate with the Wayland compositor active on your system." This backend is located in /hw/xwayland. To understand why we find this special backend here and what I mean with an Xserver backend at all, we have to first learn some Xserver fundamentals.

DIX and DDX

The hw subdirectory is the Device Dependent X (DDX) part of the Xserver. All other directories in the source tree form the Device Independent X (DIX) part. This structuring is an important abstraction in the Xserver. Like the names suggest the DIX part is supposed to be generic enough to be the same on every imaginable hardware platform. The word hardware hereby should be understood in an abstract way as being some sort of environment the Xserver works in and has to talk to, which could be the kernel with its DRM subsystem and hardware drivers or as we already know a Wayland compositor. On the other side all code, that is potentially different with respect to the environment the Xserver is compiled for is bundled into the DDX part. Since this code is by its very definition mostly responsible for establishing and maintaining the required communication channels with the environment, we can indeed call the platform specific code paths in DDX the Xserver's backends.

I want to emphasize that the Xserver is compiled for different environments, because we are now able to understand how the Xorg and Xwayland binaries we talked about in part one and that both implement a full Xserver come into existence: Autotools, the build system of the Xserver, is told by configuration parameters before compilation what the intended target platforms are. It then will use for each enabled target platform the respective subdirectory in hw to compile a binary with this platform's appropriate DDX plus the generic DIX from the other top level directories. For example to compile only the Xwayland binary, you can use this command from the root of the source tree:

./autogen.sh --prefix=/usr --disable-docs --disable-devel-docs \

--enable-xwayland --disable-xorg --disable-xvfb --disable-xnest \

--disable-xquartz --disable-xwin

Coming back to the functionality let's look at two examples in order to better understand the DIX and DDX divide and how the two parts interact with each other. Take first the concept of regions: A region specifies a certain portion of the view displayed to the user. It is defined by values for its width, height and position in some coordinate system. How regions work is therefore completely independent on the choice of hardware the Xserver runs on. That allowed the Xserver creators to put all the region code in the DIX part of the server.

Talking about regions in a view we think directly of the screen this view is displayed on. That's the second example. We can always assume that there is some sort of real or emulated screen or even multiple of them to display our view. But how these screens and their properties are retrieved is dependent on the environment. So there needs to be some "screen code" in DDX, but on the other hand we want to move as much logic as possible in the DIX to avoid rewriting shared functionality for different platforms.

The Xserver is equipped with tools to facilitate this dichotomy. In our example about screens DIX represents the generic part of such a screen in its _Screen struct. But the struct features also the void pointer field devPrivate, which can be set by the DDX part to some struct, that then provides the device dependent information for the screen. When DIX then calls DDX to do something concerning the screen, DIX also hands over a _Screen pointer and DDX can retrieve these information through the devPrivate pointer. The private resource pointer is a tool featured in several core objects of the Xserver. For example we can also find it in the _Window struct for windows.

Besides this information sharing between DIX and DDX there are of course also procedures triggered in one part and reaching into the other one. And these procedures run according to the main event loop. We will learn more about them when we now finally analyze the Xwayland DDX code itself.

The Xwayland DDX

The names of the source files in the /hw/xwayland directory already indicate what they are supposed to do. Luckily there are not many of them and most of the files are rather compact. It's quite a feat that the creators of Xwayland were able to provide X backward compatibility in a Wayland session with only that few lines of code added to the generic part of a normal Xserver. This is of course only possible thanks to the abstractions described above.

But coming back to the files here's a table of all the files with short descriptions:

| Files | Description |

|---|---|

| xwayland.h xwayland.c | Basically the entry point to everything else, define and implement the most central structs and functions of the Xwayland DDX. |

| xwayland-output.c | Provides a representation of a display/output. All its data is of course received from the Wayland server. |

| xwayland-cvt.c | Supports the output creation by generating a display mode calculated from available information. |

| xwayland-input.c | Deals with inputs provided by mice and other input devices. As you can see by its size, it's not the most straight forward area to work on. |

| xwayland-cursor.c | Makes a cursor appear. That is in a graphic pipeline often treated as a special case to reduce repaints. |

| xwayland-glamor.c xwayland-shm.c | Provide two different ways for allocating graphic buffers. |

xwayland-vidmode.c | Support for hardware accelerated video playback and older games, what is in parts not yet fully functional. |

In the following we will restrict our analysis to the xwayland.* files, in order to keep the growing length of this article in check.

Some basic structs and functions also shared with the other source files are defined in the header file xwayland.h. A good first point to remember is, that all structs and functions with names starting on xwl_ are only known to the Xwayland DDX and won't be called from anywhere else. But at the beginning of the xwayland.c file we find some methods without the prefix. They are only defined in the DIX and their implementation is required to make Xwayland a fully functional DDX.

Scrolling down to the end of the file we see the main entry point to the DDX on server startup, the InitOutput method. If you look closely you will notice a call to AddScreen, where we also hook up an Xwayland internal screen init function as one of its arguments. But it's only called once! So what about multiple screens? The explanation is, that Xwayland uses the RandR extension for its screen management and here only asks for the creation of one screen struct as a dummy, which holds on runtime some global information about the Wayland environment. We looked at this particular screen struct in the previous chapter as an example for information sharing between DIX and DDX through void pointers and that these pointers are set by the DDX.

Although it's only a dummy, we can still follow this now live in action in the hooked up init function xwl_screen_init. Here we set with the help of some DIX methods a hash key to later identify the data field again and then set the data, which is an xwl_screen struct with static information about the Wayland environment the Xwayland server is deployed in.

In the hooked up init function the later manipulation of the function pointers RealizeWindow, UnrealizeWindow and so on is also quite interesting. I asked Daniel about it, because I didn't understand at all the steps done here as well as similar ones later in the involved functions xwl_realize_window, xwl_unrealize_window and so on. Daniel explained the mechanism well to me and it is quite nifty indeed. Basically thanks to this trick, called wrapping, Xwayland and other DDX can intercept DIX calls to a procedure like RealizeWindow, execute their own code, and then go on with the procedure looking to the DIX like it never happened.

In the case of RealizeWindow, which is called when a window was created and is now ready to be displayed, we intercept it with xwl_realize_window, where an Xwayland internal representation of type struct xwl_window is allocated with all the Xwayland specific additional information, in particular a Wayland surface. At the end the request to create the surface is sent to the Wayland server via the Wayland protocol. You can probably imagine what UnrealizeWindow and the wrapped xwl_unrealize_window is supposed to do and that it does this in a very similar way.

As a last point let's look at the event loop and the buffer dispatch of possibly new or changed graphical content. We have block_handler, which was registered in xwl_screen_init to the DIX, and gets called continuously throughout the event loop. From here we call into a global damage posting function and from there for each window into xwl_window_post_damage. If we're lucky we get a buffer with hardware acceleration from the implementation in xwayland-glamor.c or otherwise without acceleration from the one in xwayland-shm.c, attach it to the surface and fire it away. In the next event loop we play the same game.

Forcing an end to this article, what we ignored in total is input handling in Xwayland and we also only touched the graphics buffer in the end. But at least the graphic buffers we'll discuss in the coming weeks exhaustively, since my Google Summer of Code project is all about these little guys.

Roman Gilg

Roman Gilg